An Argentine Adventure

Last night, Delta cancelled our flight home on the 23rd with no rebooking yet. This morning, the president of Argentina announced that all flights to and from the US, China and EU will stop as of Monday. Rather than rush to heavily-populated Buenos Aires and try to get space on an outgoing flight, we’ve opted to stay in this relatively unpopulated part of the country and shelter in place (with lots of wine).

- Email from David to family and friends on Saturday, March 14, 2020

Last week, my wife and I were staying in Cafayate, Argentina, a mile-high, small town 200 km from the nearest airport.

Located deep in the wine region of northwest Argentina, Cafayate is a quaint small town. Picture a sleepy town square lined with wine bars and restaurants. The little burg is bracketed by steep mountain ranges to the east and west and surrounded by vineyards just waiting for a wine tasting tour. Wikipedia says the town has a population of 11,000, but I’m guessing that either that census was taken at the height of tourist season or they decided to include all the stray dogs and wild burros in the count.

Although we got news updates on our phones, neither of us had seen an English-language news broadcast in ten days. Novel coronavirus seemed (and was) a world away.

When the couple running the tour told us some flights back to the US were getting cancelled, we were surprised. Argentina was planning to close their airports to incoming flights from “high-risk” countries, including the United States, for ten days.

Did we want to make a run for Buenos Aires and try to get out of the country immediately?

We looked online at the pictures of US customs with people returning from Europe stacked on top of (and coughing all over) each other, took another sip of a fine Malbec, and said, “No, thank you, we’d be happy to spend a few more days here.”

That’s when I sent the breezy email to friends and family.

Staying seemed like a good idea at first. The next day, we went to Las Nubes Bodega for a wine tasting and lunch. The little winery is perched high above Cafayate with absolutely spectacular views of the Calchaquí Valley. Every year they host a local wine harvest and grape stomp event, like the one in the 1995 Keanu Reeves movie, A Walk In The Clouds. (Las Nubes means the clouds.) This year it was cancelled due to the coronavirus.

The next day we drove along the famed Ruta Cuarenta (Route 40), a 5000km “road” that parallels the Andes, starting in the tip of Argentina and running all the way north to the border with Bolivia. The part we rode on was paved where it ran through a town and dirt the rest of the time. Bridges are optional, you ford the rivers. Also, if you see a big rock or brush in the road, that’s a marker telling you the shoulder has eroded to the point where you might fall off into the gorge below.

We had a late lunch at the Piatelli Winery, owned by a family from Minnesota. Four courses with wine pairings for each course. This is the life, we thought. The estate is brand-new and would rival anything you could find in Europe or Napa Valley in terms of facilities or food. We toasted our brilliance at staying put in beautiful Argentine wine country while the world got sucked into the tornado of the 24-hour news cycle.

The next day, we used the quincho (outdoor kitchen) at our guesthouse to host a real Argentine asado (barbeque) complete with a half-dozen different cuts of meat and a full case of wine. It was an all-day event of shopping, prepping, grilling and drinking.

Although we didn’t know it at the time, the asado was a fitting end to our vacation. On Wednesday, Cafayate shut down.

My wife and I walked to the ATM which was located across the street from our favorite heladeria (ice cream shop). She was supposed to get pesos and I was securing the ice cream. The warmup to another day in paradise.

Except the ice cream shop was closed.

I looked around the town square. All the restaurants were closed.

That evening, our tour leader talked one of the local restaurants into hosting a private dinner for our group of 12. It was sort of fun as we skulked to the restaurant in groups of two or three and sneaked in. As the waiters put paper over the windows so the cops patrolling outside couldn’t see inside, we joked about being in a 1920s speakeasy.

Things got more real as the week wore on. The original shutdown went from a precautionary measure to a 10-day quarantine. Salta, the nearest big city 200 km away, reported a case of COVID-19. All the towns in the province started aggressive lockdown procedures with police checkpoints.

On Friday, I saw a police vehicle circling the town square announcing in Spanish for all residents to stay indoors. The President of Argentina announced all flights into the country would be suspended for 30 days.

Meanwhile, back at home, our children, both twenty-somethings, were not pleased with our life choices. We had kept up the “it’s all gonna be fine” line even as things worsened around us, but I pushed it too far.

When I forwarded an email to my kids from a well-known blogger about staying calm in chaos, I received a sternly worded – and extremely well-written — reply from my 21-year-old son lecturing me about making good choices:

I can appreciate that rational thought driven by facts and logic rather than emotions often leads to better decision making. However, you’ve consistently underestimated the effects, scale, and severity of the virus on our calls and texts…I love you both. Please fully acknowledge the situation you’re in, and work to remedy it.

I was somewhere between embarrassed by the reprimand and proud of his logic. (I know good writing when I see it.) His sister picked up the torch in a separate email:

I am immensely frustrated and worried. If either of your own parents delayed their return as long as you two did you would be beside yourselves.

You know what? They were right.

In the background, our hosts were working overtime. Since the Argentine airline is state-owned, it was shut down, meaning there was no way for us to get back to Buenos Aires. However, they had found a COPA Air flight out of Salta to Panama leaving at 2AM on Sunday morning. The only problem was we needed to travel 200 km through a series of locked-down towns to get to Salta airport. The local police were taking their quarantine duties very seriously.

All indications were this was the last possible flight out of Salta for the next month. If one of the towns refused to allow us to pass, we’d miss our flight. If our flight got cancelled while we were in transit to the airport, we would not be allowed to come back to Cafayate.

Thoughts of the Tom Hanks movie Terminal Man played in my head.

The drive from Cafayate to Salta takes three hours. We left ten hours before our flight with a police escort out of town.

[Side note: the road to Salta is bumpy. How bumpy? I got 4000 steps on my Fitbit just from sitting on the bus.]The drive up the Quebrada de las Conchas (Ravine of the Shells) is stunning (and dusty). Sharp peaks on either side of the winding highway. Red rocks blazing in the afternoon sun. Geological formations that boggle the mind. Think the Rockies combined with the Grand Canyon, but better.

We were armed with local health forms proving we had been in Argentina more than 14 days, a letter from the President of Argentina saying that any foreigner with a valid plane ticket should be allowed safe passage to the nearest airport, and a contact at the US Embassy on speed dial.

The first two towns reviewed the paperwork and let us pass, but as we got closer to Salta, the scrutiny increased. At a little burg called Coronel Moldes, the local police refused to let us pass. Instead, we were escorted by bicycle police to the local hospital.

Juan Mujica from the US Embassy argued with the police chief until the chief started shouting. We understood that they wanted to do a health check on one of the passengers in the van. Ron, a fit guy in his sixties, volunteered. He came back, telling us that they did temperature, blood pressure, pulse and general health questions.

Then they started taking us in one by one. The tension in the van ramped up dramatically.

I called Juan and updated him. “No problem,” he told me. “It’s just routine.”

I mean, what was he supposed to say? We didn’t have a choice in the matter. We were ten people who spoke minimal Spanish at the mercy of El Capitan of Policia Coronel Moldes.

But the reality was pretty grim. We’d been traveling together as a group for three weeks. None of us seemed sick, but what if one of us popped a fever? Would the whole group be quarantined?

Everyone in the bus breathed a huge sigh of relief when the local doctor signed off on our health certificates and we got an ambulance escort out of town. We passed through another half-dozen police checkpoints with the usual hassle and finally arrived at Salta Airport.

A new wrinkle: we noticed the airport checkpoint was manned by officers in two different uniforms. Our best guess was airport police and local police, but they seemed to be having a lively discussion on who had jurisdiction over this van full of gringos.

After an agonizing wait, we received a police escort to the terminal. We made it!

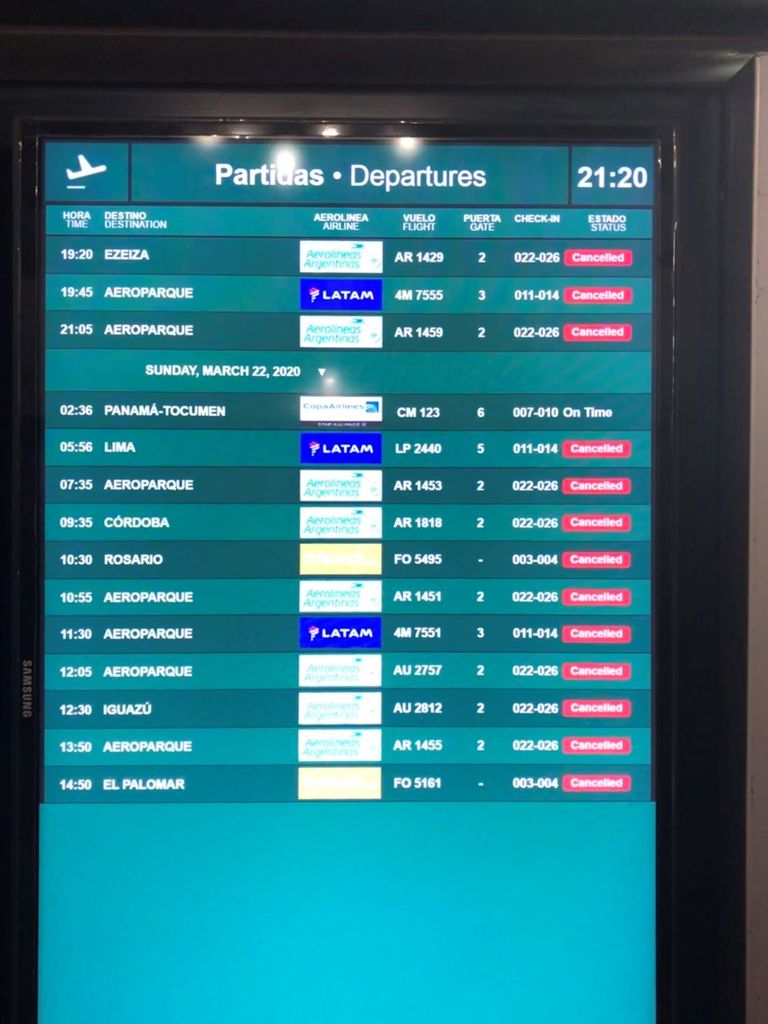

The terminal was completely empty. Of the dozen flights scheduled to depart on Saturday night and Sunday, ours was the only one not cancelled.

The only passengers on the Boeing 737-800 that took off that night were the ten members of our group plus two others. There were as many crew on the flight as passengers.

Thirty-six hours and four airports later, we touched down in Minneapolis. As a former corporate road warrior, I’ve flown thousands of times, but I have never been more glad to be home.

That’s not the end of the story, of course. My wife and I are self-quarantining at home with our college age son. Since I work from home, it’s not really an inconvenience for me, but the fact that we can’t go anywhere means the pace of life has slowed for all three of us.

This enforced pause has also afforded me a chance to reflect on the experience. As I said above, I’ve traveled a lot and found myself in some interesting situations, but the Argentine escape was different.

Being an American citizen of a certain socio-economic status has many benefits. For starters, we are raised with a sense of optimism, an attitude often reinforced by our movies and literature.

We expect things to work out in our favor. When I travel abroad, I used to view my US citizenship like a shield. Not a shield in the sense of entitlement (although some Americans act like that), but in the sense that my government has my back. If I were to get into trouble – real trouble – Uncle Sam will ride to the rescue.

Argentina made me reexamine that attitude. Our odyssey in Argentina was not like a scene from the movie Argo. It could have gone very, very badly – and not for the reasons you think.

I wasn’t worried some evil, power-drunk Argentine police chief wanted to lock us up. I was more worried some well-meaning Argentine police chief might believe locking us up was the best way to keep his citizens safe. (Remember, in the not too distant past, tens of thousands of Argentine citizens “disappeared” under a military dictatorship. This stuff is still in the news down there.)

We were extraordinarily lucky. We had people, like our kids, who loved us and insisted we get home right away. We had tour leaders Kent and Christine Zimmerman working round the clock to secure plane tickets and coordinate with the local police. We had Juan Mujica and Nancy Schmidt-Jones from the US Embassy working behind the scenes. The COPA flight out of Salta was basically empty. I’m willing to bet they had something to do with the flight being available on Sunday morning.

Without that team, my wife and I would still be sitting in Cafayate.

Even with all that support, things could have gone sideways in a hurry. There are thousands of American citizens still stranded in South America that don’t have a Kent, Christine, Juan, or Nancy.

The most remarkable aspect of this whole experience was not how fast the situation changed. It’s how preventable it was.

In hindsight, it is painfully apparent that the still-growing COVID-19 impact on the United States is a massive intelligence leadership failure. The virus didn’t come out of nowhere. The situation has been unfolding in China for nearly six months now. The first case of COVID-19 in the US was reported on 22 January. Our intelligence services knew what it had done to China and was starting to do to Italy.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a national defense issue, except the invaders are not Russians or North Koreans missiles, it’s a virus. Our government ignored the warning signs and wasted our most precious resource in the battle against the virus: time.

But that ship has sailed, as the saying goes. What I’m left with is learning from the Argentina experience, so here’s what I (re)learned:

- Surround yourself with good, competent people like Kent and Christine, Juan, and Nancy.

- The world has changed. Your US citizenship is not a shield. Don’t wait for the State Department to advise you on travel plans.

- Listen to your kids. Sometimes they know what they are talking about.

NOTE: When I think back over the last few weeks, the days all sort of run together. The events depicted here are my best recollection of reality as backed up by emails, pictures, and contemporaneous notes. If there are errors, they are mine and mine alone.