Tag Archives for " Two Navy Guys and a Novel "

Two Navy Guys Talk Modern Day Piracy on the High Seas

Welcome back to Two Navy Guys and a Novel, the blog series where you get to watch two ex-Navy guys write a military thriller called Weapons of Mass Deception. New to the series? No problem, I’ve gathered all the episodes in one convenient place on my website.

Welcome back to Two Navy Guys and a Novel, the blog series where you get to watch two ex-Navy guys write a military thriller called Weapons of Mass Deception. New to the series? No problem, I’ve gathered all the episodes in one convenient place on my website.

The thing about writing a book is that you have to make choices about how much detail to put in your story. Too much information—no matter how interesting—can slow down a fast-paced story like nobody’s business. In many cases, a whole lot of research gets boiled down to one or two sentences in the final draft.

Spoiler alert: we have a scene in WMD about Somali pirates. It turns out our very own JR has some inside knowledge about modern day piracy that will never make it into our story. But that doesn’t stop us from telling you all about it here.

Here’s JR:

In September 2008, I attended the 1st Maritime Security Symposium, sponsored by the German Navy, in Hamburg, Germany. The main focus of the Symposium was on piracy, specifically the rising threat from Somali pirates.

Piracy has been around as long as there have been ships, but the closest modern equivalent to Somali piracy can be found on the other side of Indian Ocean. For centuries, pirates operating out of Aceh province, Indonesia, have been attacking commercial ships in the Strait of Malacca, the narrow shipping lane between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

So strong had the pirates grown with the money they’d made that “pirate cartels” had formed to share in the booty. Think Pirates of the Caribbean, but without the comedy or romance. Purely business, and a violent one at that.

At the symposium, the head of the Malaysian Navy discussed the cooperative efforts by Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore to combat piracy. According to this admiral, the governments of those three nations launched a joint counter-piracy initiative to successfully defeat the pirate threat.

Maybe.

One Way to Defeat Pirates…

Another event also contributed to the rapid depletion of Aceh-based pirates, and it had nothing to do with the best efforts of the navies from the countries mentioned above.

The day after Christmas in 2004, the Indian Ocean Tsunami struck, “estimated to have released the energy of 23,000 Hiroshima-type atomic bombs, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).” That tsunami wiped out all the coastal villages in Aceh province, on the island of Sumatra, where the pirates lived and based their operations.

The day after Christmas in 2004, the Indian Ocean Tsunami struck, “estimated to have released the energy of 23,000 Hiroshima-type atomic bombs, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).” That tsunami wiped out all the coastal villages in Aceh province, on the island of Sumatra, where the pirates lived and based their operations.

As is typical at large bureaucratic conferences, there was a lot of talk and no shortage of ideas about how combat the Somali pirates, which had become a real issue by late 2008. Still, something bugged me about the discussion: no one addressed how Somali piracy came into existence in the first place.

That disconnect lingered for another year until I attended a lecture back in Finland.

Unintended Consequences

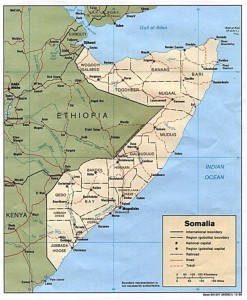

In late 2009, halfway through my tour as U.S. Naval Attaché, I attended a lecture hosted by the Finnish Defence Forces. The guest speaker described a perfect storm of unrelated events that led to the rise of Somali piracy. Given the narrow Straits of Malacca, the Aceh pirate problem seemed natural, but Somalia? Look at a map and you see nothing but open ocean off the Somali coast.

The government of Somalia collapsed in 1991. From that time forward, it was known in diplomatic circles as a “failed state.” Civil war erupted, food was used as a weapon between the Somali clans, and international involvement had little impact in helping the Somali people rebuild their government and their nation.

The government of Somalia collapsed in 1991. From that time forward, it was known in diplomatic circles as a “failed state.” Civil war erupted, food was used as a weapon between the Somali clans, and international involvement had little impact in helping the Somali people rebuild their government and their nation.

In international law, there is a boundary known as the EEZ, or Exclusive Economic Zone, a 200 nautical mile line that extends from a nation’s shore out to sea, as defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Most nations observe these boundary lines as part of normal international economic cooperation.

During the fifteen years when Somalia had no government, there was no capability for the nation to protect their economic interests, namely the fisheries that were the lifeblood of the coastal Somali people. International fishing fleets were free to harvest as much fish from the ocean off Somalia as their vessels could carry, and within 10 years, the seas were badly depleted. These were people who had known only fishing as their way of life. Asking them to quit fishing and to take up carpentry was simply not a realistic option.

(Editorial note: International law is a tricky subject, fraught with exceptions and counter-arguments. For example, not all nations, including the US, are signatories to the UN convention mentioned here. Other nations ignore the UN Convention when it suits their national interests. And there are always commercial entities that will ignore international boundaries when they can get away with it. That said, the main point stands: Somalia was unable to protect her economic interests at sea and other countries took advantage of her weakness.)

Teach a Man to Fish and You’ll Feed Him for the Rest of His Life

The United Nations is not without resources or the ability to offer solutions to nations in need. In the case of Somalia, the World Food Program chose to “teach a fisherman to fish,” rather than simply give the coastal villages food handouts. A reasonable idea, right? Give the fishermen the tools they need to be successful at fishing and you do not need to place the Somali fishing villages into the “addicted to WFP food stocks” column.

So, the WFP provided new, larger boats, engines, and supplies to the fishing villages so they could fish further out to sea.

Except, there were no fish to catch, or damn few of them anyway. The international fishing fleets had wiped out the stocks, even many hundreds of miles out to sea. This put the village elders in a bit of a pickle. Too few fish, and too many people trying to catch them.

A New Line of Business

It did not take long for some enterprising young men, angry with the economic situation they faced, and with quick and easy access to weapons (Somalia was once the illegal weapons trade capital of the world) to hit upon a new way to use their fancy new boats.

It did not take long for some enterprising young men, angry with the economic situation they faced, and with quick and easy access to weapons (Somalia was once the illegal weapons trade capital of the world) to hit upon a new way to use their fancy new boats.

Why not board the vessels of wealthy people at sea, and demand a ransom? So, they gave it a try, and succeeded beyond their wildest imaginations. Every time they took over a ship, they were given ransom money, either by the insurance companies covering the vessel, or the company, or the wealthy private yacht owner.

Very quickly the Somali piracy problem turned into a huge money-making scheme for the young men of the coastal villages – about a thousand young men in all – and each time maritime insurance companies paid ransom, more young men were recruited into the “business.” Piracy operations expanded further and further into the Indian Ocean, in search of more and bigger prey. As was shown in Captain Phillips, pirate cartels were formed and “mothership” tactics employed to enable pirate attacks as far as 1,000 nautical miles off the Somali coast.

Within a few years, piracy became the boom industry of Somalia, reaching its height between 2008 and 2010. In the movie Captain Phillips, which occurred in 2009, you get a taste of the US response. But things were already changing by that point, the international community, using U.S. Navy CTF 151 and the EU-sponsored Operation ATALANTA, began to have an effect on seizures. There are also significant independent operations by India, Russia, and China.

The WMD Connection

As I mentioned above, Somali pirates play a small, but important, role in our story. If you want to ship something from the Persian Gulf to the Americas, you need to go around the Horn of Africa…and pass by the coast of Somalia. We just might have a scene like that in the book.

As always, if you'd like to get in touch with us, you can drop us a comment below or an email to twonavyguys@davidbruns.com.

David Bruns is the creator of the sci-fi series The Dream Guild Chronicles, and one half of the Two Navy Guys and a Novel blog series about co-writing the military thriller, Weapons of Mass Deception. Check out his website for a free sample of his work.